Finally, you can see the finish line. You’ve spent months if not years writing your book, sent it through multiple rounds of editing, from the developmental to copyediting, and now it’s in the final stage of proofreading before being sent to the printer. All that’s left is to review the proofs and append that index. No sweat. You know what you wrote, how hard can it be to run a quick search in Word for the key ideas and alphabetize them? Heck, even a grad student can do it!

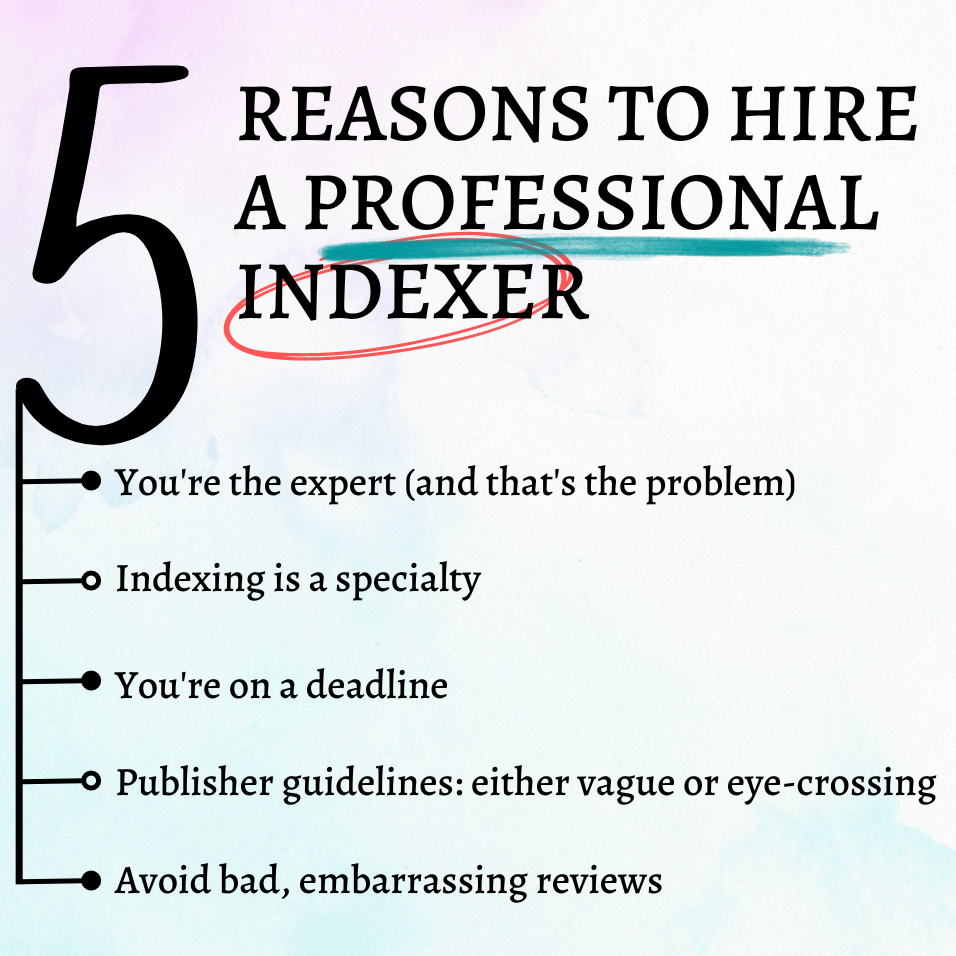

You could do that, but both you and your publisher are likely to be unhappy with the end result (keep an eye out for some up-coming posts on bad indexes and what makes them bad). It may seem like a waste of money, but hiring a professional indexer (not your grad student or your colleague who indexed their own book) is worth it more ways than one. Here are 5 Reasons Why You Should Hire a Professional Indexer.

- You’re the expert (and that’s the problem).

- You know your book inside and out. You sweated over every word, every concept. Of course you know all the key terms. But the index isn’t for you, and it isn’t just for your colleagues and other experts in your field. Even the most specialized monograph is going to attract readers who are tangentially interested in what you have to say, whether for a research project or pure curiosity. The index should speak to them as well.

- A professional indexer indexes with the reader in mind, and that means experts in the field who know the terminology you’re using, new-comers just starting out who won’t know to look up “phospholipid bilayer” (they’ll search for “cell membrane” or just “fat”), and those who’ve read your book and are coming back to it trying to find a particular passage or reference. Keeping all those readers and their search terms in mind is a lot to juggle.

- And then there are the horror stories I’ve heard from fellow indexers. The author hired them to write the index, they did, only to have it come back with an angry email about why Important Scholar isn’t in the index, or why Major Idea isn’t there. Indexer apologizes, searches, can’t find either, asks for help from the author. Turns out, Important Scholar and Major Idea got cut in editing. And it’s perfectly natural for such things to slip the author’s mind! After all, you’d included them in the conference paper and the journal article you wrote prior to the book. It’s hard to keep track, just like I always struggled to remember which jokes and anecdotes I’d told which section of my various courses. The indexer indexes what’s in the book. No more, no less.

- Indexing is a specialty.

- Indexers are made, not born. It’s not a topic covered in much depth even in editing courses, in part because it’s fairly niche, with its own specialized vocabulary: metatopic, array, main head, subhead, locators (including both undifferentiated and unruly locators), cross-references, qualifiers and glosses, spans, curves, double-posting, patterns, strings, embedding, mark-up, passing mentions, scattering, gathering… You get, I think, the idea.

- Like all specialties, indexing has sub-specialties. There’s embedded vs traditional, linked vs static, closed vs open. Some indexes require a controlled vocabulary, others don’t. How you index a trade book is different from a scholarly monograph, which in turn is different from a textbook, cookbook, journal, encyclopedia, legal text, and art catalogue.

- But I’m not writing all those kinds of books, you say, I’m just writing my monograph so I can get tenure. Great! All the more reason to be sure your book has a good index. I invite you to take down a dozen books in your field from the library stacks and have a look at the indexes. You’ll probably see some differences running through them. Some might have page numbers in bold on occasion. Others may sort all titles like 1984 to the very start of the index, while others place it as though it were written “nineteen eighty-four,” sticking it among the Ns. Some probably have two indexes: subject and name. Maybe there’s also a geographic index. Some books will index the illustrations and figures, others won’t. In other words, that’s a lot of decision-making to do, even before you get to the essential task of choosing terms, thinking about how ideas link together through cross-references, and all the other aspects that make an index not a concordance but a supplement to your book that enhances the reader’s experience.

- You’re on a deadline and have proofs to review.

- With all those decisions facing you, do you really have time to write your own index? Publishing deadlines are tight. The printer has you booked for a particular slot, and delays can be costly (and costly delays mean unhappy editors at your press). Nevermind that proofs will be coming in for your to review. Also, there’s the committee meeting coming up, marking to finish, office hours to hold, and a new lecture to write. Indexing isn’t your job, so why let it take over all your time and energy?

- Every indexer goes at their own speed, but a professional indexer will typically ask for 2-3 weeks for a standard scholarly monograph. Do you have 2-3 weeks to devote to this?

- Publisher guidelines are either vague or eye-crossing.

- Some publishers say “provide a suitable index for your manuscript.” Okay. What does that mean exactly? Others will give you far more guidance, down to the line width and number of lines, special markup for each type of entry, number of acceptable undifferentiated locators, and punctuation to precede and follow every line. Helpful? Absolutely, if you know what all of that means and have the software to easily implement it with a few clicks of the mouse. Hair-pullingly irritating when you’re trying to do everything in Word.

- You’ll avoid bad, embarrassing reviews like these.

- From a book on the devil, published in the 2010s: “Finally, the four-page single-level index is a joke…what possible use is the entry ‘Satan’ with 84 undifferentiated page numbers, or ‘Devil’ with 102, or ‘demon’ with 79, out of a total of 190 text pages? You’d think a scholar would know the importance of a good index.”

- From a book on books, published in the 2000s: “…[it’s]blighted only by an absurd index which makes it almost impossible to work out who are the artists responsible unless one is already familiar with their work.”

- From a mathematics textbook, published in the 1990s: “This secondary math textbook has an index that is not very helpful. What value are more than 180 page references for the entry ‘Science’? What use is a similar quantity of page numbers for the entry ‘Industry’?”

- From a book on the information revolution, published in the 1990s: “The index is disgraceful.” (Yikes!)

Thinking a professional indexer isn’t such a bad idea after all? Great! How do you find one? One who has some knowledge of your field, and won’t mistake Mary Ann Radcliffe for Ann Radcliffe in your index?

Professional indexing societies include a register of indexers, where you can often search by specialty and quickly find those indexers who’ve experience with, let’s say, medieval history, musicology, astrophysics, or Australian law.

Indexing Society of Canada/Société canadienne d’indexation (ISC/SCI)

American Society for Indexing (ASI)

Australian and New Zealand Society of Indexers (ANZSI)

Association of Southern African Indexers and Bibliographers (ASAIB)

Nederlands Indexers Netwerk (NIN) / Netherlands Indexing Network

Deutsches Netzwerk der Indexer (DNI) / German Network of Indexers