05 March 2024

One of the hardest parts of indexing to do well is cross-references (those see and see also lists that accompany some headings). Figuring out not just when to point the reader from one place to another, but what kind of pointing is appropriate is not straight-forward. Generally speaking, cross-references act like a combination of thesaurus and suggested reading list. If you looked at the concept “manipulation” in a book on philosophy, you might also be interested in knowing about the related idea of “coercion.” If you looked at “Nixon, Richard” in a political history book, you may also want to read into “Watergate.” Those may seem obvious, but what if the topic is more obscure or specialized? Would someone who isn’t an expert on the Hundred Years War, when reading a book on its causes, know that if they’re looking up Robert d’Artois they would do well to also look at Jeanne de Divion or Mahaut d’Artois? And when should the spider-web of cross-references stop? Should the entry on Nixon point to Agnew and CREEP and Barbara Jordan and contempt of Congress and impeachment and Ford and Hunt and McCord and and and… At that point, the entire index might just get re-indexed in the cross-references.

So how does an indexer figure out which elements to connect and which to leave for the reader to discover on their own?

There is no one answer to this. A lot of it comes down to understanding how the author has structured the book and paying attention to the connections and thoughts that occur to us as readers while we move through the text. When I’m reading a book about, for example, gender representation in superhero comic books, I may wonder when indexing “costumes” how the artistic depictions relate to superhero sexuality, and so I’ll cross-reference to that idea, even if the author never makes an explicit argument about costume choices and sexual representation on the page.

I recently indexed a book that presented unique challenges for cross-references. For the rest of this post, I’m going to examine what some of those challenges were and how I solved them.

This book, by Jason Brown, had four interrelated metatopics: St Antoninus, his Summa, and what his Summa had to say on trade and the merchants who engaged in trade. To make things even more complex, the book was divided between a critical analysis of Antoninus on trade as written in the Summa and an edited transcription of the relevant chapters of the Summa with a facing-page English translation. Let’s look at three of these metatopics to see how I used the cross-references to guide the reader.

Metatopic: Antoninus

The entire book was ostensibly about him, but it wouldn’t do to put everything under his name. So I gave him two main arrays (that is, main headings + subheadings). “Antoninus” covered his biographical details while immediately below the em-dash heading “writings” (i.e., “Antoninus: writings”) focused on his various books.

Antoninus: appointment as auditor general of the tribunal of the Rota, 29; archbishop of Florence, 29, 36, 38-45; biographies of, 7-10; Black Death, actions in response to, 40-1; Buonomini lay confraternity, 34; Catherine of Siena’s influence, 23, 24, 29; character, 11, 12, 20, 41-2; childhood, 10-11, 12-13; on Council of Basel, 30; death, 44-5; Decretum memorized, 19-20; Dominican order, attraction to, 12, 13, 16-17; Dominican order, entering, 20, 21; education, 12-13; Eugenius IV, relationship with, 29-30, 38-9; Giovanni Dominici’s influence, 16-17, 20-1, 58; Great Schism, 26-7; heresy, combatting, 41-2; independence from political interests, 42-3; legacy of his writings, 46-9; Medici and, 30-1, 32, 42-3, 160; monastery of San Marco, 30, 31, 32-3, 34-5, 45, 46, 56-7; movement between Dominican houses, 27, 28, 29; Observant Reform Movement, 26, 32; pastoral care, 35, 36-8, 39-41; popularity of printed works, 46-7; Renaissance, engagement with, 154; teaching, 61, 222; veneration as saint and canonization, 8, 19, 45-6; voted for as pope, 44; writing career, 28, 34-5, 36, 40, 63

———writings. See also Summa (Antoninus): Chronicles (Chronica), 16-17, 35, 51-2; Confessionale (“Defecerunt”), 51; Confessionale (“Omnis mortalium cura”), 28, 37, 50-1, 96-8; manuals of confession, 28, 50-1; Medicina dell’anima (“Curam illius habe”), 37, 51; Opera a ben vivere (The Art of Living Well), 40, 41; prior writings incorporated into Summa, 95-101; Tractatus de censuris, 88-9, 98-9; types of, 37, 50-1

I only used one cross-reference here, and that was to the Summa, since the focus of the author’s analysis concerned it.

Metatopic: Summa

The Summa was a complicated idea to index. Brown’s book provided a significant amount of analysis of this text as both physical object and written product. Then there was the analysis of the content and the transcription/translation. All of this needed to be indexed, leading to the Summa having a stacked structure of ten arrays.

Summa (Antoninus)

———autographs

———editorial principles of author

———translation by author, note on

———2.1.16 on fraud

———2.1.17 fraudulent practices

———3.8.1 on merchants and workers

———3.8.2 contracts

———3.8.3 on traders and bankers

———3.8.4 kinds of workers

The first array, “Summa (Antoninus),” cross-referenced from Antoninus’s writings, covers the general information about the text. The next array, “autographs,” concerns a set of manuscripts bearing Antoninus’s own hand, followed by two short arrays on how Brown approached the task of editing and translating the text. The final six arrays were for the six chapters of the Summa that concerned trade and were the ones transcribed and translated at the end of the book.

I relied most heavily on cross-references when it came to these arrays for the six chapters. The index already contained conceptual entries for things such as fraud, profit, monopolies, etc. Double-posting those ideas under the chapter arrays would have significantly lengthened the index without being much use to the reader. I reasoned that someone who wanted to know what Antoninus had to say about, for example, usury was far more likely to look under U than under Summa (Antoninus): 3.8.3 on traders and bankers. So for each of these arrays, I kept the subheadings limited to direct analysis of the chapter as such by Brown as well as a page range off the main heading that told the reader where to find the sustained critical analysis and the English translation (the latter page numbers given in bold). In effect, I created a more specialized table of contents, kind of like the nineteenth century penchant for paragraph TOC entries (chapter seven, in which our hero engages with venerated authorities, applies a doctrinal approach, focuses on Florence, has a go at scholastic moral theology, and structures his day):

———3.8.3 on traders and bankers, 207-19, 411-47. See also assurances; exchange banking; fraud; merchants; trade; usury; individual authorities; authorities for, critical discussion, 208, 212, 213, 214, 234-5; doctrinal and casuistic approach, 208, 232; Florentine focus, 211-12, 213; scholastic method of moral theology, 234; structure of chapter, 207-8, 411

A reader wanting to know what Antoninus was up to in chapter 3.8.3 could see at a glance from the cross-references what topics were covered (assurances, exchange banking, etc.). With the page range of 411-47 for the translation, the reader could then follow these cross-references to the desired concepts, knowing which elements of usury applied to this chapter (usury: exchange banking and; vs interest; mental usury; restitution; in the Roman curia).

At first blush, this may appear to violate the indexing principle of not making the reader have to do a lot of flipping around in the index to find what they’re after. But at thirty-two pages for a run-in index, I judged it better to not end up with a bloated index. After all, the reader is most likely to go to U if they’re interested in usury. Placing all of that information under 3.8.3 would be both long-winded and unhelpful.

But how do these cross-references help a reader grasp the structure of the index, and thus the book? Let’s follow just one line of cross-references to see how they can bring the reader deeper than they might otherwise go.

Taking 3.8.3 as our example, let’s follow the cross-reference “exchange banking.” It’s not likely to be a term a new reader of the book would look up, making it qualitatively different from the “usury” example above. Already, then, the cross-reference at the metatopic has drawn the reader deeper into the text. A reader looking at what 3.8.3 has to say about exchange banking finds that it covers several ideas: bills of exchange as loans, currency exchange, dry exchange, exchange by bill, mediation of simony, mental usury, petty exchange, exchange in the Roman curia, and usurious activities. That’s a lot! and those are only the subheadings relevant to the discussion in 3.8.3. Then there are the cross-references off exchange banking (banking and bankers; merchants), bringing the reader to other, related parts of the index (the first being something of a horizontal relationship, the second of the “readers interested in exchange banking also looked at merchants” variety).

Metatopic: Trade

Finally, there’s trade, which like the other two topics could have the entire book fall under its array. But that won’t do. Unlike the first two metatopics, it didn’t require the stacked em-dash structure of related arrays cascading down the page, but it couldn’t just point to other terms via cross-references and have nothing for itself. Some ideas, such as the purpose of trade and the distastefulness of trade, didn’t lend themselves to being main headings in their own right (both because there’s no good term other than “trade” that a reader would be likely to look up and because the concept had too few mentions in the book to get pulled out for special treatment).

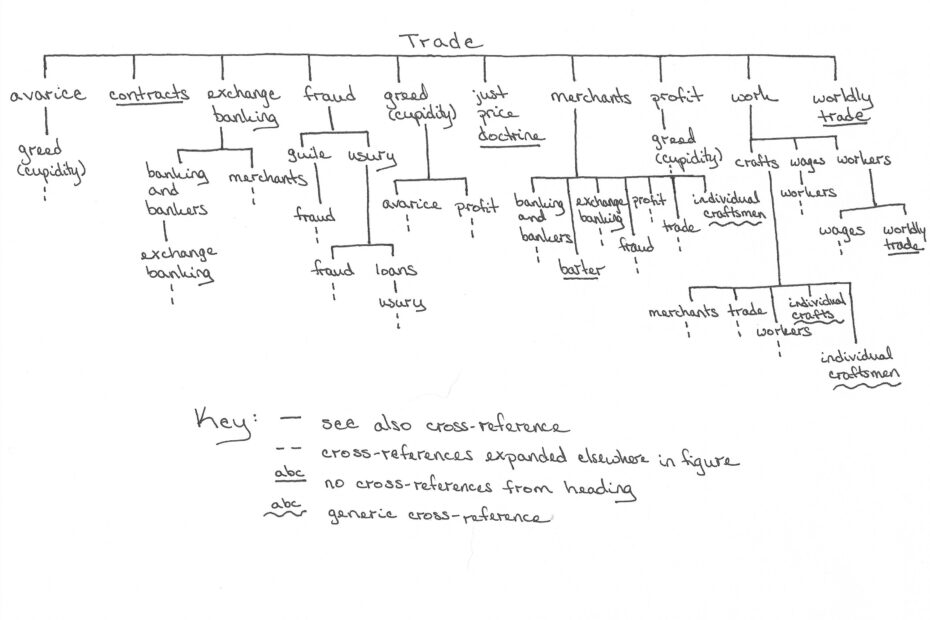

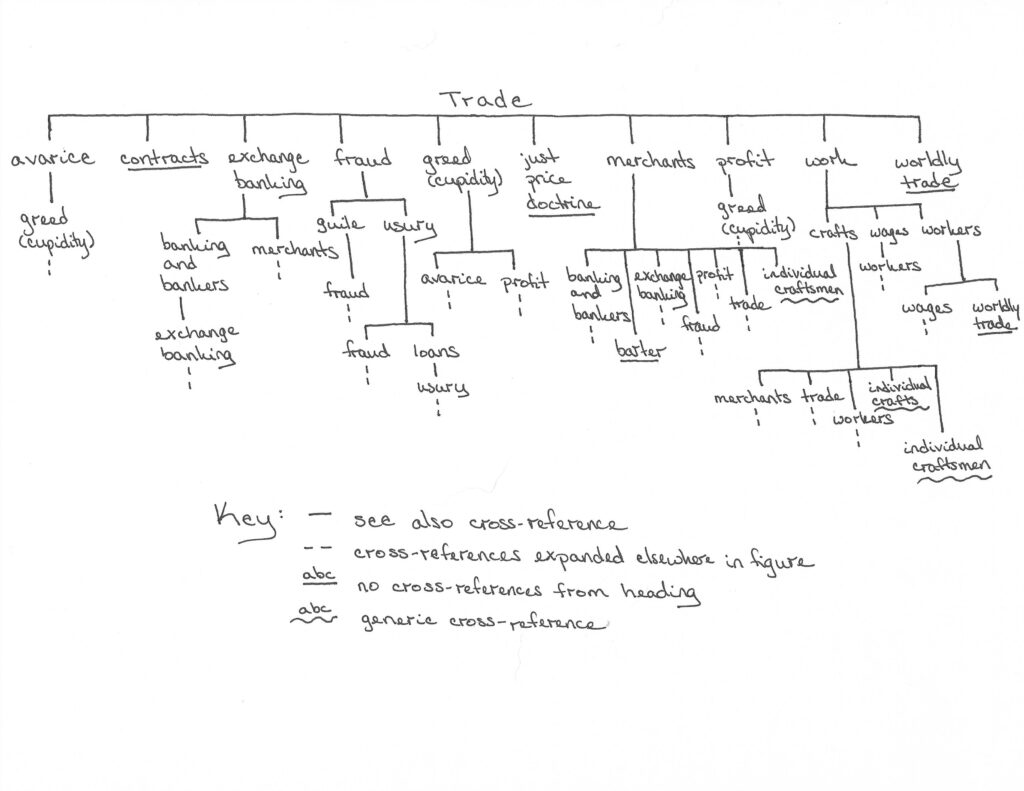

Such instances aside, however, there were a lot of ideas that trade could point to, both ones that a reader might think up on their own (merchants, profit) and ones they might not (avarice, just price doctrine). Unlike with the chapters of the Summa, where reproducing the concepts under the array would have been a defensible choice (if a poor one, in my opinion), reproducing the ideas related to trade underneath trade would lead to the situation I outlined with Richard Nixon above. At this metatopic in particular, the cross-references act as nodes in a hierarchical network, reaching down to more specialized ideas, each node going a bit deeper while connecting the reader to interrelated concepts.

The cross-reference has become a family tree.

By way of concluding remarks, I’m going to borrow from Do Mi Stauber’s excellent Facing the Text to point out some of the relationships between the cross-references. The cross-references off the metatopics (the focus of this blog post) are general-to-specific references: they go from a big idea to a narrower one. Some of those ideas (“contracts”) are so narrow that they don’t have any further cross-references, while others are mini-metatopics in themselves, or supermain headings in Margie Towery’s phrasing: “work” is an example of a supermain heading.

A common type of cross-reference is the associative cross-reference: a reader who has looked up one term would probably be interested in the other one (the shopping algorithm of cross-references, if you will). In a book on trade, the reader interested in “greed (cupidity)” would probably be interested in “profit.” Similarly, within medieval theology, “avarice” and “greed (cupidity)” are closely related by not synonymous ideas, so they deserve distinct headings but should point to each other.

The other style of cross-reference worth noting are those with a squiggly line beneath the heading in the figure. These are general cross-references. That is, they do not point to a specific heading but instruct the reader to look up ones that they come up with. General cross-references are tricky creatures, as I am assuming that the reader can think of types of “individual craftsmen” (potters, cobblers, apothecaries, smiths, etc.) and “individual merchants” (animal brokers, wool merchants, silk merchants, etc.). There are so many of these individuals running around Brown’s book that listing them all out would be tedious for both indexer and reader. More than that, only a select few (such as wool merchants and silk merchants) have enough page numbers after the headings to warrant subheadings. For most of the craftsmen and merchants, their page numbers are covered under the subheadings found off “merchants” and “crafts.”

A final type of cross-reference present in this figure is the specific-to-general cross-reference. Generally speaking, I avoid making a specific term point to a more general one, but occasionally it can be helpful. Here, “trade” points to “work” (as trade is a kind of labor), which in turn points to “crafts” (a form of work), which points to “trade” (a purpose for the work of crafting). Why have I broken this “rule” of indexing? First, because as we can see from my example, the conceptual meaning of “trade” is not stable and, depending on the meaning invoked it can be an over-arching idea or a subset of another one. Second, because a reader is going to come into the text at different points. Sure, the title of the book, St Antoninus of Florence on Trade, Merchants, and Workers, tells the reader that trade is a main idea, but what if they are particularly interested in artisan crafts? The index will point them to the less restrictive “crafts,” and from there they may end up at the heading for “trade.”

Cross-references are, in the end, a balancing act. Too many and the reader is caught in a sticky spider’s web, unable to move forward due to the plethora of options without clear guidance. Too few, and the reader is attempting to climb a cargo net at summer camp, feet constantly slipping through holes while they struggle to find their way in an index that doesn’t provide enough guidance.